Wales has been mapped, measured, and reimagined for over four centuries, with each generation of cartographers bringing new techniques, priorities, and perspectives to the task of representing this small but geographically complex nation. From the earliest county surveys of the Elizabethan era to the precision of modern Ordnance Survey sheets, the story of Welsh cartography reflects broader currents in science, politics, and national identity.

The Elizabethan Pioneers

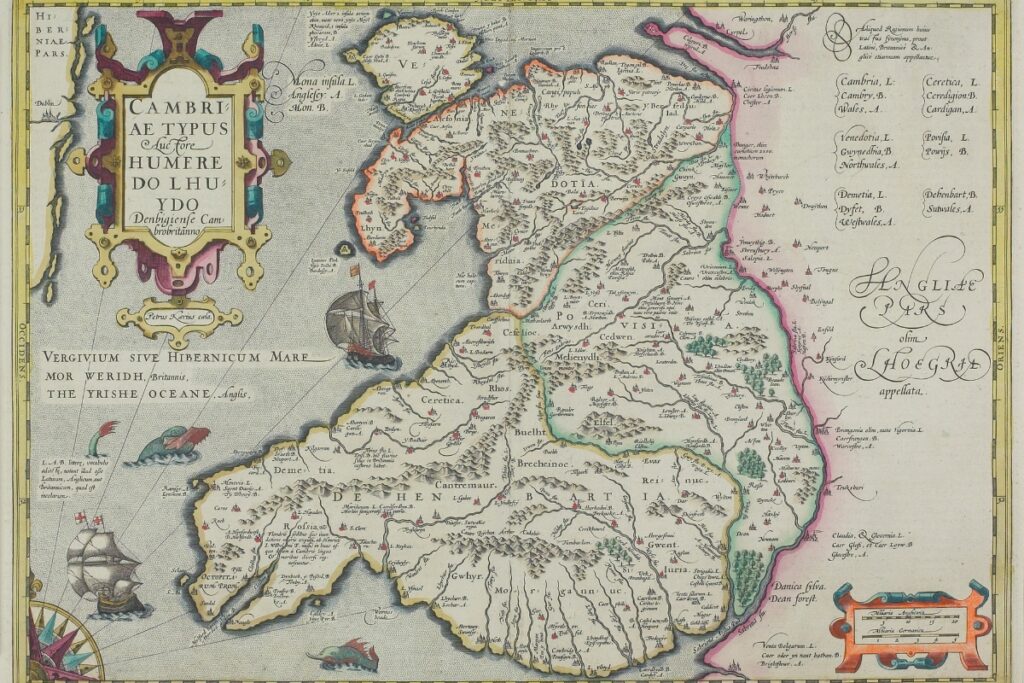

The systematic mapping of Wales began during the reign of Elizabeth I, when Christopher Saxton produced his landmark atlas of England and Wales between 1574 and 1579. Saxton’s county maps were the first detailed surveys of Welsh territory, showing towns, rivers, hills, and forests with remarkable accuracy for the period. His work was commissioned partly for administrative and military purposes—the Tudor state needed to know its territory—but the resulting maps also became objects of beauty and prestige.

Saxton depicted Wales across several sheets covering the traditional counties: Anglesey, Caernarfonshire, Denbighshire, Flintshire, Merionethshire, Montgomeryshire, Cardiganshire, Radnorshire, Breconshire, Pembrokeshire, Carmarthenshire, Glamorgan, and Monmouthshire. His representations of the Welsh mountains, shown as clusters of sugar-loaf hills, established a visual convention that would persist for over a century.

John Speed followed in the early seventeenth century with his Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain (1611-12), which included detailed maps of each Welsh county. Speed added town plans to his county maps—his inset plans of towns like Caernarfon, Brecon, and Cardiff provide invaluable records of urban Wales at the start of the Stuart period. Speed’s maps were more decorative than Saxton’s, featuring elaborate cartouches, coats of arms, and figures in contemporary dress.

The Age of Improvement

The eighteenth century brought new ambitions and new methods to Welsh cartography. Estate mapping flourished as landowners sought accurate surveys of their holdings, and these detailed local maps captured field boundaries, buildings, and land use with unprecedented precision. Many survive in Welsh archives today, offering intimate portraits of agricultural landscapes that have since been transformed.

At the national scale, the most significant development was the creation of maps designed to support economic improvement and travel. Emanuel Bowen and Thomas Kitchin produced popular county maps showing roads, distances, and market towns—practical information for a society increasingly on the move. Their maps reflected an Enlightenment confidence in measurement and rational organisation.

Lewis Morris, a Welsh polymath from Anglesey, undertook detailed coastal surveys of Wales in the 1730s and 1740s. His charts of harbours, bays, and navigational hazards served the maritime economy and represented some of the most accurate hydrographic work of the period. Morris combined practical surveying skill with a passionate interest in Welsh language and antiquities—a reminder that cartography in Wales has often been intertwined with questions of cultural identity.

Ordnance Survey and the Nineteenth Century

The systematic mapping of Wales by the Ordnance Survey began in the early nineteenth century and fundamentally transformed how the country was represented. What had begun as a military project to map vulnerable coastal areas gradually expanded into a comprehensive national survey at multiple scales.

The first Ordnance Survey one-inch maps of Wales appeared in the 1830s and 1840s, followed by the extraordinarily detailed six-inch and twenty-five-inch surveys from mid-century onwards. These large-scale maps recorded every building, field boundary, footpath, and stream. They documented the industrial transformation of south Wales—the spread of collieries, ironworks, railways, and workers’ housing—as well as the more gradual changes in rural areas.

For historians today, the nineteenth-century Ordnance Survey maps are an unparalleled resource. They capture Wales at a moment of dramatic change: the old agricultural landscape still visible beneath the spreading infrastructure of industrial modernity. Place names on these maps, recorded by English surveyors with varying degrees of accuracy, have become subjects of considerable scholarly and popular interest.

Maps and Welsh Identity

The relationship between cartography and national identity has been particularly charged in Wales. Maps do not simply record territory; they shape how that territory is understood and imagined. The county boundaries shown on Saxton’s and Speed’s maps became administrative realities that endured for centuries. The linguistic boundary between Welsh-speaking and English-speaking areas, mapped with increasing precision from the nineteenth century onwards, became central to debates about language policy and cultural survival.

Some maps have been explicitly nationalist in purpose. The twentieth century saw the creation of maps celebrating Welsh heritage—ancient kingdoms, castles, literary associations, and Celtic connections. These cultural maps presented Wales not as a collection of English-style counties but as a nation with its own coherent geography and history.

The 1974 local government reorganisation, which replaced the thirteen historic counties with eight new ones bearing medieval Welsh names (Gwynedd, Clwyd, Powys, Dyfed, and so on), was itself an exercise in cartographic reimagining. Though further reorganisation in 1996 created the current twenty-two principal areas, debates about how Wales should be divided and mapped continue to carry political and cultural weight.

Digital Cartography and the Present

Contemporary mapping of Wales combines satellite imagery, GPS technology, and digital databases to create representations of unprecedented accuracy and accessibility. Ordnance Survey data underpins everything from smartphone navigation to planning applications. Online platforms allow anyone to explore Welsh landscapes from their desktop, zooming from national overviews to street-level detail.

Yet older maps retain their fascination. Archives and libraries across Wales hold collections spanning five centuries, and digitisation projects have made many historically significant maps freely accessible online. The National Library of Wales maintains an extensive cartographic collection, and organisations like the Welsh Encyclopaedia and local history societies continue to research and publish on the history of Welsh mapping.

For those exploring Wales today, understanding the cartographic history of the country adds depth to the experience. The coastline you see on your phone screen was first charted by Lewis Morris nearly three hundred years ago. The mountain paths marked on your walking map follow routes first surveyed by Ordnance Survey teams in the Victorian era. And the county names on road signs echo boundaries drawn by Tudor administrators who needed to know—and to control—this corner of their realm.

Wales has been mapped for purposes of taxation and military control, for agricultural improvement and industrial development, for tourism and national pride. Each generation of maps tells us as much about the mapmakers and their times as about the landscape itself. In that sense, the history of Welsh cartography is inseparable from the history of Wales.