Santes Dwynwen Day, celebrated on 25 January each year, is the Welsh festival of love honouring St Dwynwen, the patron saint of lovers. Often called the Welsh Valentine’s Day, this ancient celebration predates its February counterpart and has experienced a remarkable revival in recent decades, becoming a cherished expression of Welsh identity and romantic tradition. This comprehensive guide covers everything you need to know about Santes Dwynwen Day, from the tragic legend of the saint herself to how the day is celebrated today, the symbolism and customs associated with Welsh love traditions, and why this uniquely Welsh festival deserves recognition far beyond the borders of Wales.

A Welsh Celebration of Love

Every year on 25 January, while the rest of the world waits for February’s Valentine’s Day, Wales celebrates its own festival of love. Santes Dwynwen Day, named for the fifth century saint who became the patron of Welsh lovers, offers a distinctly Welsh alternative to the commercialised celebrations that dominate the international calendar. This is a day rooted in ancient legend, Celtic spirituality, and the Welsh landscape itself, yet it speaks to universal experiences of love, loss, and hope.

The revival of Santes Dwynwen Day represents one of the most successful cultural recoveries in modern Welsh history. A generation ago, few Welsh people knew of Dwynwen or marked her feast day. Today, the celebration has established itself as a genuine part of Welsh life, embraced by couples, families, and communities as an opportunity to express love in a way that honours Welsh heritage while remaining thoroughly contemporary.

The story of St Dwynwen herself contains the elements of great romantic tragedy: forbidden love, divine intervention, impossible choices, and ultimate sacrifice for the sake of others. Her legend connects the celebration to specific places in the Welsh landscape, most notably the island of Llanddwyn off the coast of Anglesey, where she established her church and where pilgrims sought her blessing for centuries.

For those seeking an alternative to the mass produced sentiment of commercial Valentine’s Day, Santes Dwynwen Day offers something more meaningful. The celebration invites reflection on love in all its complexity, honours a specifically Welsh tradition, and connects romantic expression to landscape, language, and legend in ways that generic celebrations cannot match.

The Legend of St Dwynwen

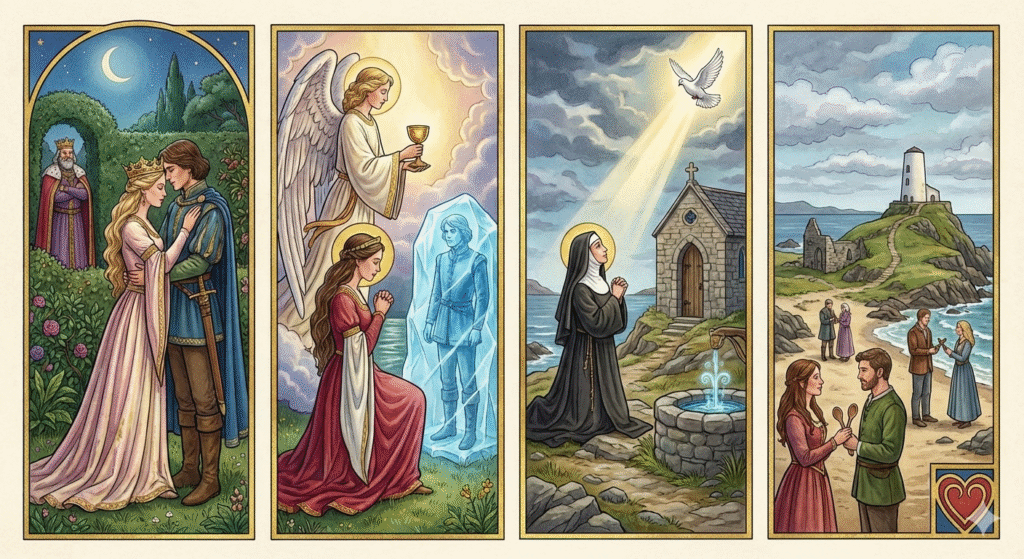

The story of Dwynwen is one of the great romantic legends of Wales, a tale of love, heartbreak, and transformation that has resonated across fifteen centuries. Like many saints’ legends, the story exists in multiple versions, but the essential narrative remains consistent across tellings.

Dwynwen’s Origins

Dwynwen lived in the fifth century, a daughter of Brychan Brycheiniog, a legendary king who ruled over the Welsh kingdom of Brycheiniog in what is now the Brecon Beacons area of south Wales. Brychan was famously prolific, credited with fathering numerous children, many of whom became saints themselves. The Welsh term “plant Brychan” (children of Brychan) refers to this remarkable family of holy men and women who spread Christianity across Wales and beyond.

As a princess of the royal household, Dwynwen would have lived in comfort and security, her future presumably mapped out according to the political calculations of her father’s court. Marriage alliances between noble families formed the currency of early medieval politics, and daughters of kings served as valuable assets in cementing relationships between kingdoms.

But Dwynwen’s heart followed its own path, with consequences that would transform her from princess to saint.

The Forbidden Love

The legend tells that Dwynwen fell deeply in love with a young man named Maelon Dafodrill. The accounts vary regarding Maelon’s status, some identifying him as a prince in his own right, others as a young nobleman of lesser rank. What remains consistent is that their love was forbidden.

The most common version of the legend states that Brychan had already promised Dwynwen in marriage to another man, making her love for Maelon impossible to fulfil. The political calculations of the court took precedence over the desires of the heart, and Dwynwen found herself caught between duty to her father and love for Maelon.

In some versions of the legend, Maelon responds badly to Dwynwen’s inability to marry him. Some accounts suggest he attempted to force himself upon her when she explained she could not be his wife. Others portray his reaction as angry rejection or bitter despair. The details vary, but the outcome is consistent: the love between Dwynwen and Maelon could not survive the obstacles placed before it.

Divine Intervention

Heartbroken by the impossibility of her love, Dwynwen prayed to God for release from her suffering. She asked to be freed from the torment of her feelings for Maelon and to forget the love that could bring her only pain.

God responded by sending an angel who appeared to Dwynwen bearing a potion. Upon drinking the potion, Dwynwen found her feelings for Maelon transformed, her passionate love replaced by peaceful detachment. But the potion had an unexpected effect on Maelon himself, who was turned to ice, frozen in place as a consequence of the divine intervention.

The transformation of Maelon troubled Dwynwen despite her own release from love’s torment. She had not wished harm upon the man she had loved, only freedom from her own suffering. The sight of Maelon frozen prompted her to pray again, this time asking for his release.

The Three Wishes

In response to her continued prayers, God granted Dwynwen three wishes. The legend holds that she chose the following:

First, she wished for Maelon to be thawed and released from his frozen state, restored to life and freedom.

Second, she wished that she might never again desire marriage, freeing herself from the possibility of experiencing such heartbreak again.

Third, she wished that she might become the patron of true lovers, helping others find happiness in love even though she herself had renounced it.

These three wishes encapsulate the essence of Dwynwen’s sainthood. She chose compassion for the man who had been harmed through her prayers. She chose a celibate life dedicated to God rather than risk further romantic suffering. And she chose to dedicate her existence to helping others achieve the happiness in love that she had been denied.

Life on Llanddwyn Island

Following her transformation from princess to saint, Dwynwen withdrew from worldly life to become a nun. She eventually established herself on a small tidal island off the western coast of Anglesey, known today as Llanddwyn Island (Ynys Llanddwyn).

The island provided the solitude appropriate to religious contemplation while remaining connected to the mainland at low tide. Dwynwen built a church on the island and lived out her days in prayer and devotion. The church she founded became a site of pilgrimage, attracting those who sought her intercession in matters of love.

Dwynwen died around 465 AD, and her feast day was established as 25 January, the date now celebrated as Santes Dwynwen Day. After her death, the church on Llanddwyn continued to function as a pilgrimage site, with a sacred well on the island reputed to have powers of divination regarding matters of the heart.

The Sacred Well and Pilgrimage Traditions

Llanddwyn Island became one of the great pilgrimage sites of medieval Wales, drawing visitors who sought St Dwynwen’s blessing on their romantic hopes and fears. The traditions that developed around the island and its sacred well provide fascinating insight into Welsh attitudes toward love and divine intercession.

Ffynnon Dwynwen

The sacred well known as Ffynnon Dwynwen (Dwynwen’s Well) became the focus of pilgrimage activity on the island. Like many holy wells in Celtic Christianity, the well was believed to possess special properties that connected the physical and spiritual worlds.

Pilgrims visiting the well sought answers to questions about their romantic futures. The most famous divination practice involved observing the movements of a sacred eel or fish that was believed to inhabit the well. The creature’s movements in response to the pilgrim’s inquiry would be interpreted as predictions about the success or failure of their romantic hopes.

If the eel or fish moved actively in response to a question, this was interpreted as a favourable omen, suggesting that the lover’s suit would prosper. If the creature remained still or moved away, the omen was considered unfavourable. Other variations of the practice involved placing items of clothing or personal effects on the water and observing how they floated or sank.

Pilgrimage Practice

The pilgrimage to Llanddwyn followed patterns common to medieval Welsh holy sites. Pilgrims would approach the island on foot, crossing the tidal causeway that connects Llanddwyn to the mainland of Anglesey. The journey itself formed part of the spiritual practice, with the liminal passage between mainland and island representing the crossing from ordinary life into sacred space.

Upon reaching the island, pilgrims would visit the church, make offerings, and pray to St Dwynwen for assistance in their romantic concerns. The offerings collected at the shrine generated significant income during the medieval period, indicating the popularity of the pilgrimage and the importance of love concerns to the visiting faithful.

The site attracted not only those seeking new love but also those wishing to strengthen existing relationships, heal rifts between lovers, or seek guidance regarding romantic decisions. The comprehensive nature of Dwynwen’s patronage made her relevant to anyone touched by matters of the heart.

Decline and Revival

The pilgrimage tradition at Llanddwyn declined following the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century. The suppression of Catholic practices, including the veneration of saints and pilgrimage to holy wells, reduced Llanddwyn from a thriving pilgrimage site to an abandoned ruin.

The church buildings fell into decay, though their remains are still visible on the island today. The sacred well continued to be visited by some local people, but the formal pilgrimage tradition effectively ended. For centuries, Dwynwen and her island faded from mainstream Welsh consciousness.

The modern revival of interest in Santes Dwynwen Day has brought renewed attention to Llanddwyn Island. Contemporary visitors are more likely to be tourists or couples celebrating the day of love than formal pilgrims, but the connection between the saint, the island, and matters of the heart continues to draw people to this beautiful and atmospheric location.

Llanddwyn Island Today

Llanddwyn Island remains one of the most beautiful and evocative locations in Wales, combining natural splendour with historical resonance in a setting that perfectly embodies the romance associated with St Dwynwen.

The Island Setting

Llanddwyn Island extends from the southwestern corner of Anglesey into the waters of Caernarfon Bay. The island is technically a peninsula for most of the tidal cycle, connected to the mainland by a narrow strip of sand that floods only at the highest tides.

The landscape is dramatic, with rocky outcrops rising from sandy beaches and views extending across the water to the mountains of Snowdonia on the mainland. The peaks of Yr Wyddfa (Snowdon) and its neighbours provide a spectacular backdrop, their outlines changing with the light and weather throughout the day.

The beaches around Llanddwyn consistently rank among the finest in Wales, with crystal clear water and golden sand that would not be out of place in more tropical locations. On calm days, the sea takes on turquoise and emerald hues that seem improbable in Welsh waters.

Historic Remains

The ruins of St Dwynwen’s church remain visible on the island, though reduced to fragments after five centuries of abandonment. The Celtic cross that marks the site provides a focal point for visitors seeking connection with the saint and her legend.

Other historic structures on the island include a row of nineteenth century cottages that once housed pilots who guided ships through the treacherous waters of the Menai Strait. A lighthouse and associated buildings from the same period add to the island’s character.

The remains of Ffynnon Dwynwen, the sacred well, can still be identified, though the well no longer functions as it did during the pilgrimage era. Visitors seeking the romantic resonance of the site often leave tokens and offerings at the well and cross, continuing in modified form traditions that stretch back centuries.

Visiting Llanddwyn

Llanddwyn Island is accessible via Newborough Forest on Anglesey. The approach involves walking through the forest and across Newborough Beach, a journey of approximately one mile from the car park to the island.

The walk forms an appropriate prelude to visiting this special place, with the gradual transition from forest to beach to island creating a sense of pilgrimage even for secular visitors. The views open out as you emerge from the forest, with the island visible across the expanse of beach.

The island itself offers walking routes that visit the historic remains, explore the rocky coastline, and provide viewpoints across the surrounding waters. The combination of history, legend, and natural beauty makes Llanddwyn one of the essential destinations in Wales.

Visiting on or around Santes Dwynwen Day has become popular, though the island can be busy and parking limited on 25 January. Those seeking a more contemplative experience may prefer to visit on quieter days while still honouring the connection to Dwynwen and her feast.

The History of Santes Dwynwen Day

The celebration of Santes Dwynwen Day has experienced a remarkable trajectory, from medieval pilgrimage tradition through centuries of obscurity to vigorous modern revival.

Medieval Observance

During the medieval period, St Dwynwen’s feast day would have been observed as part of the regular cycle of saints’ days that structured the religious year. The 25 January would have been marked with special services at churches dedicated to Dwynwen and particularly at Llanddwyn Island itself.

The pilgrimage tradition meant that the feast day drew visitors to Llanddwyn from across Wales and beyond. The income generated from pilgrims’ offerings indicates that the celebration was substantial, with Dwynwen ranking among the more popular Welsh saints.

The nature of medieval observance combined religious devotion with popular custom. Formal religious services would have been complemented by more informal practices, including the divination rituals at the sacred well and doubtless various customs that have not survived in the historical record.

Post Reformation Decline

The Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century dealt a severe blow to the veneration of saints in Wales and throughout Britain. The rejection of Catholic practices, including pilgrimage, the cult of saints, and the use of holy wells for divination, removed the institutional support for Dwynwen’s feast day.

The physical infrastructure of the cult was destroyed or abandoned. The church on Llanddwyn fell into ruin, the pilgrimage ceased, and the feast day lost its public observance. Dwynwen herself faded from popular consciousness, remembered only in local tradition and occasional antiquarian interest.

For approximately four centuries, Santes Dwynwen Day was effectively forgotten. While some awareness of the saint persisted in Welsh language literature and local folklore, the feast day was not widely observed as either a religious or secular celebration.

Twentieth Century Rediscovery

The twentieth century brought renewed interest in Welsh identity and heritage, creating conditions for the rediscovery of traditions like Santes Dwynwen Day. The Welsh language movement, growing since the early twentieth century and intensifying from the 1960s onwards, sought distinctive Welsh alternatives to English cultural imports.

Scholars and cultural activists began drawing attention to St Dwynwen and her feast day as a specifically Welsh celebration of love, predating and offering an alternative to Valentine’s Day. The appeal was obvious: a romantic celebration rooted in Welsh legend, connected to a beautiful Welsh landscape, and expressed through the Welsh language.

The gradual revival began in the latter decades of the twentieth century, with poets, writers, and cultural organisations promoting awareness of the saint and encouraging celebration of her feast day. Cards, gifts, and expressions of love on 25 January began appearing in Welsh speaking communities.

Twenty First Century Revival

The twenty first century has seen Santes Dwynwen Day achieve mainstream recognition in Wales. What began as a revival project promoted by cultural activists has become a genuine popular celebration embraced across Welsh society.

Several factors contributed to this success:

Commercial adoption saw Welsh businesses producing cards, gifts, and products specifically for Santes Dwynwen Day, making celebration practical and visible.

Social media allowed the celebration to spread rapidly, with Welsh speakers sharing greetings and traditions online and introducing non Welsh speakers to the festival.

Institutional support from Welsh language organisations, schools, and media helped normalise the celebration and embed it in the annual calendar.

Cultural confidence in Welsh identity provided a receptive audience for a distinctively Welsh celebration of love.

Today, Santes Dwynwen Day is observed throughout Wales and among Welsh communities worldwide. While it has not displaced Valentine’s Day, it has established itself as a complementary celebration with particular resonance for those who value Welsh heritage and identity.

How Santes Dwynwen Day is Celebrated

Contemporary celebration of Santes Dwynwen Day combines romantic expression with cultural affirmation, blending universal themes of love with specifically Welsh traditions and symbols.

Cards and Greetings

The exchange of cards and greetings forms the core of modern Santes Dwynwen Day celebration, following the pattern established by Valentine’s Day but with distinctively Welsh character.

Welsh language cards are widely available, featuring traditional sentiments and contemporary designs. Common phrases include:

“Dydd Santes Dwynwen Hapus” (Happy St Dwynwen’s Day)

“Dwi’n dy garu di” (I love you)

“Cariad” (Love, also used as a term of endearment)

“Fy nghariad” (My love)

The cards often incorporate Welsh symbols and imagery, including lovespoons, dragons, daffodils, and images of Llanddwyn Island. The visual language distinguishes Santes Dwynwen Day cards from generic Valentine’s Day products and reinforces the Welsh character of the celebration.

Digital greetings have become increasingly popular, with social media posts, e-cards, and text messages spreading Santes Dwynwen Day wishes across digital networks. The hashtag #SantesDwynwen trends on Welsh social media each 25 January.

Gifts and Tokens

Gift giving on Santes Dwynwen Day follows romantic conventions while often incorporating Welsh elements:

Lovespoons are traditional Welsh tokens of affection, carved wooden spoons with intricate decorative patterns. The lovespoon tradition predates Santes Dwynwen Day’s modern revival but has become closely associated with the celebration. Different carved symbols carry specific meanings, allowing lovespoons to communicate complex sentiments.

Welsh food and drink make popular gifts, including Welsh cakes, bara brith (fruit bread), and Welsh whisky or gin. The emphasis on Welsh provenance reinforces the cultural dimension of the celebration.

Jewellery featuring Welsh symbols such as the dragon, the daffodil, or lovespoon designs offers lasting tokens of affection.

Flowers are given as on any romantic occasion, sometimes with emphasis on daffodils or other flowers associated with Wales, though the daffodil’s later blooming season makes this a March rather than January flower.

Experiences such as trips to Llanddwyn Island, meals at Welsh restaurants, or visits to Welsh cultural attractions provide alternatives to material gifts.

Romantic Celebrations

Couples celebrate Santes Dwynwen Day with romantic meals, outings, and expressions of affection similar to Valentine’s Day:

Restaurant meals are popular, with many Welsh restaurants offering special Santes Dwynwen Day menus featuring Welsh produce and romantic settings.

Visits to Llanddwyn Island provide a pilgrimage experience for couples seeking to connect with Dwynwen’s legend in her sacred place.

Expressions of love through poetry, song, and personal communication honour the literary dimension of Welsh romantic tradition.

Proposals and declarations sometimes choose Santes Dwynwen Day as the occasion for significant romantic commitments, adding personal meaning to the national celebration.

Community and Cultural Events

Beyond personal romantic celebration, Santes Dwynwen Day occasions various community and cultural events:

School activities introduce children to the legend of Dwynwen and the traditions of Welsh romantic expression, with card making, storytelling, and Welsh language activities.

Cultural events including concerts, poetry readings, and performances celebrate Welsh language and heritage with romantic themes.

Church services at some Welsh churches mark the feast day with religious observance, though this remains less common than secular celebration.

Media coverage ensures widespread awareness, with Welsh television, radio, and online media providing programming related to the day.

Welsh Love Traditions and Symbols

Santes Dwynwen Day connects with broader traditions of Welsh romantic expression, including customs and symbols that distinguish Welsh approaches to love from generic international practices.

The Lovespoon Tradition

The Welsh lovespoon (llwy garu) represents one of the most distinctive traditions of romantic expression in any culture. These intricately carved wooden spoons have been exchanged as tokens of affection in Wales for centuries, their decorative elements communicating specific meanings through a vocabulary of symbols.

The tradition dates from at least the seventeenth century, though its origins may be older. Young men would carve lovespoons to present to the women they wished to court, the skill and care demonstrated in the carving reflecting the sincerity and depth of their feelings.

The symbols carved into lovespoons carry established meanings:

Hearts represent love, the universal symbol adapted to the Welsh medium.

Horseshoes signify good luck and wishes for prosperity.

Bells indicate marriage and the hope for wedding bells.

Wheels symbolise support and the promise to work hard.

Links and chains represent loyalty and the bonds of love.

Keys signify the keys to the heart or the security of home.

Celtic knots represent eternal love through their endless interlocking patterns.

Dragons incorporate Welsh national identity into romantic expression.

Contemporary lovespoons range from simple designs to extraordinarily complex pieces that may take months to carve. While few modern suitors carve their own lovespoons, the tradition of giving purchased lovespoons continues, and the craft itself is maintained by skilled artisans throughout Wales.

Caru and Cariad

The Welsh language provides distinctive vocabulary for expressing love that carries cultural resonance beyond mere translation:

Cariad is the Welsh word for love and for loved one, serving both as noun and term of endearment. Calling someone “cariad” in Wales carries warmth and intimacy that transcends its literal meaning.

Caru is the verb to love, used in expressions from casual affection to profound declaration. “Dwi’n dy garu di” (I love you) carries the weight of Welsh linguistic heritage in its expression of universal feeling.

Anwylyd means beloved or dear one, another term of endearment that enriches Welsh romantic vocabulary.

Serch refers to affection or romantic love, distinguishing passionate attachment from the broader applications of cariad.

The persistence and revival of Welsh language romantic vocabulary represents a form of cultural resistance, maintaining distinctive expression against the homogenising pressure of English language dominance. Using Welsh terms of endearment, whether or not one is a fluent Welsh speaker, connects romantic expression to cultural identity.

Welsh Love Poetry

Wales possesses a rich tradition of love poetry stretching back to the medieval period, when court poets (beirdd) composed elaborate verses following complex metrical rules. This tradition provides a literary heritage for contemporary Welsh romantic expression.

The cywydd, a verse form developed in the fourteenth century, was frequently used for love poetry. The strict metrical and alliterative requirements of traditional Welsh poetry created a framework within which poets demonstrated skill while expressing feeling.

Dafydd ap Gwilym, the greatest Welsh medieval poet, is particularly celebrated for his love poetry. His verses, addressed to women including Morfudd and Dyddgu, combine technical virtuosity with emotional intensity and humour. His work remains influential in Welsh literary culture and provides models for contemporary poets working in both traditional and modern forms.

The tradition continues through subsequent centuries to the present day, with contemporary Welsh poets addressing themes of love in both Welsh and English. Santes Dwynwen Day has encouraged new compositions, with poets producing work specifically for the occasion.

Romantic Customs

Beyond lovespoons and poetry, Welsh tradition includes various customs associated with romance and courtship:

Bundling (caru yn y gwely) was a courtship practice allowing couples to spend nights together fully clothed, becoming acquainted while maintaining at least technical propriety. The practice, common in rural Wales into the nineteenth century, allowed couples to develop relationships during the limited free time available in agricultural communities.

Bidding weddings (neithior) were community celebrations where guests brought gifts to help establish the new household. The reciprocal obligations created by these gifts wove marriages into the fabric of community mutual support.

Mari Lwyd, though not specifically a romantic tradition, involves elaborate rituals of sung verses and counter verses that demonstrate the Welsh cultural emphasis on verbal wit and poetic expression that also characterises romantic traditions.

Santes Dwynwen Day and Welsh Identity

The revival and celebration of Santes Dwynwen Day connects intimately with questions of Welsh identity, language, and cultural confidence.

Cultural Distinctiveness

Santes Dwynwen Day provides Welsh people with a romantic celebration that is authentically their own rather than an import from elsewhere. While Valentine’s Day has global reach, Santes Dwynwen Day belongs specifically to Wales, rooted in Welsh legend, Welsh landscape, and Welsh language.

This distinctiveness matters in a context where Welsh cultural identity exists alongside and sometimes in tension with dominant English language culture. Celebrating Santes Dwynwen Day makes a statement about cultural allegiance and the value placed on Welsh heritage, even for those who are not fluent Welsh speakers.

The celebration demonstrates that Welsh culture offers alternatives to international homogenisation, that distinctive traditions can be revived and made relevant to contemporary life, and that cultural identity can be expressed through joyful celebration rather than only through political assertion.

Language and Celebration

The Welsh language (Cymraeg) stands at the heart of Santes Dwynwen Day celebration. While the day can be observed by non Welsh speakers, the natural medium of expression is Welsh, and participation encourages engagement with the language.

Cards, greetings, and gifts typically feature Welsh language text, familiarising recipients with Welsh phrases even if they are not fluent speakers. The phrase “Dydd Santes Dwynwen Hapus” has become recognisable even to those with minimal Welsh, spreading language awareness through celebration.

For Welsh speakers, Santes Dwynwen Day provides an occasion to use their language for intimate expression, affirming Welsh as a living language suitable for all dimensions of human experience including romantic love. The celebration normalises Welsh as a language of the heart.

For learners and non speakers, the day offers accessible entry points to Welsh language and culture. Learning a few phrases for Santes Dwynwen Day, giving Welsh language cards, or exploring the legend of Dwynwen creates connections that may deepen over time.

Contemporary Relevance

The success of Santes Dwynwen Day’s revival demonstrates that traditional culture can adapt to contemporary circumstances. The celebration has embraced modern media, commercial channels, and changing social norms while maintaining connection to its historical and legendary origins.

Young Welsh people have adopted Santes Dwynwen Day enthusiastically, sharing greetings on social media, celebrating with friends and partners, and incorporating the day into their annual calendars. The celebration feels contemporary rather than antiquarian, a living tradition rather than a museum piece.

The commercial dimension, sometimes criticised as diluting authentic tradition, has actually helped spread awareness and make celebration practical. The availability of cards, gifts, and products specifically for Santes Dwynwen Day makes participation easy for those who might not otherwise engage with Welsh cultural traditions.

Santes Dwynwen Day Beyond Wales

While Santes Dwynwen Day is fundamentally Welsh, awareness and celebration have spread beyond Wales, carried by diaspora communities and cultural interest.

Welsh Diaspora

Welsh communities around the world observe Santes Dwynwen Day as a connection to their heritage:

Patagonia in Argentina, where a Welsh speaking community has existed since 1865, maintains strong cultural ties with Wales. Santes Dwynwen Day provides an occasion for celebrating both romantic love and Welsh identity in this distant community.

The United States, Canada, Australia, and other countries with significant Welsh heritage populations see Santes Dwynwen Day observances organised by Welsh societies and cultural organisations.

Welsh expats throughout the world use social media to share Santes Dwynwen Day greetings, maintaining connection to Welsh culture despite geographical distance.

International Interest

Beyond the Welsh diaspora, Santes Dwynwen Day has attracted interest from those drawn to Celtic culture, alternative traditions, or simply the appeal of a romantic legend set in beautiful landscape:

Celtic enthusiasts appreciate Santes Dwynwen Day as part of the broader Celtic cultural heritage, alongside Irish, Scottish, Breton, and other Celtic traditions.

Cultural tourists visiting Wales around 25 January may encounter and participate in celebrations, carrying awareness back to their home countries.

Romantics seeking alternatives to commercialised Valentine’s Day find in Santes Dwynwen Day a celebration with deeper roots and more distinctive character.

Practical Information for Celebrating

For those wishing to observe Santes Dwynwen Day, whether in Wales or elsewhere, practical options abound.

Cards and Gifts

Welsh shops and online retailers stock Santes Dwynwen Day cards and gifts, particularly in the weeks leading up to 25 January. Searching online for “Santes Dwynwen Day cards” reveals numerous options.

Lovespoons can be purchased from Welsh craft shops, tourist locations throughout Wales, and online retailers. Prices range from modest for simple designs to substantial for complex artisan pieces.

Welsh food and drink make appropriate gifts and can be ordered online for delivery anywhere. Welsh cakes, bara brith, Welsh cheeses, and Welsh spirits offer tasty expressions of cultural connection.

Visiting Llanddwyn Island

For those able to visit Wales, Llanddwyn Island provides the ultimate Santes Dwynwen Day destination:

Getting there: The island is accessed via Newborough Forest on Anglesey. Drive to the Newborough Beach car park (postcode LL61 6SG), then walk approximately one mile through the forest and across the beach to the island.

Parking: The car park can be extremely busy on and around 25 January. Arriving early or visiting on alternative days is advisable.

The walk: The route is straightforward but involves walking on sand and potentially crossing wet areas. Appropriate footwear is essential.

Tides: While the island is accessible at most tidal states, very high tides can cover the connecting strip. Check tide times before visiting.

Facilities: Minimal facilities are available on the island. Bring food, water, and appropriate clothing.

Celebrating at Home

Those unable to visit Wales can still observe Santes Dwynwen Day meaningfully:

Exchange cards and gifts with Welsh character or themes.

Prepare Welsh food for a romantic meal, with recipes readily available online.

Learn about Dwynwen and share her story with loved ones.

Use Welsh greetings even if only a few phrases.

Watch Welsh films or listen to Welsh music as part of the celebration.

Welsh Language Resources

For those wishing to incorporate Welsh language into their celebration:

“Dydd Santes Dwynwen Hapus” (Happy St Dwynwen’s Day) is pronounced approximately “deethe san-tess dwun-wen hap-ees”

“Dwi’n dy garu di” (I love you) is pronounced approximately “dween duh ga-ree dee”

“Cariad” (Love / Darling) is pronounced approximately “kar-ee-ad”

Online pronunciation guides and Welsh language learning resources can help with accurate pronunciation for those unfamiliar with Welsh.

Frequently Asked Questions About Santes Dwynwen Day

What is Santes Dwynwen Day?

Santes Dwynwen Day is the Welsh festival of love, celebrated on 25 January each year. Named after St Dwynwen, the Welsh patron saint of lovers, it is sometimes called the Welsh Valentine’s Day.

When is Santes Dwynwen Day?

Santes Dwynwen Day is celebrated on 25 January, the feast day of St Dwynwen.

Who was St Dwynwen?

St Dwynwen was a fifth century Welsh princess who, according to legend, suffered heartbreak in love and subsequently devoted her life to God, becoming the patron saint of lovers. She established a church on Llanddwyn Island in Anglesey, where she died around 465 AD.

How do you pronounce Santes Dwynwen?

Santes Dwynwen is pronounced approximately “san-tess dwun-wen” with the emphasis on the first syllable of each word. The “wy” in Dwynwen is pronounced similar to the “oo” in “good” followed by a short “i” sound.

Is Santes Dwynwen Day the same as Valentine’s Day?

No, Santes Dwynwen Day and Valentine’s Day are separate celebrations. Santes Dwynwen Day is specifically Welsh, occurring on 25 January, while Valentine’s Day is celebrated internationally on 14 February. Many Welsh people celebrate both days.

How do you say Happy St Dwynwen’s Day in Welsh?

Happy St Dwynwen’s Day in Welsh is “Dydd Santes Dwynwen Hapus” (pronounced approximately “deethe san-tess dwun-wen hap-ees”).

How do you say I love you in Welsh?

I love you in Welsh is “Dwi’n dy garu di” (pronounced approximately “dween duh ga-ree dee”) or more simply “Rwy’n dy garu di.”

What is a Welsh lovespoon?

A Welsh lovespoon is a decorative wooden spoon carved with intricate patterns and symbols, traditionally given as a token of romantic affection. The tradition dates from at least the seventeenth century, and different carved symbols carry specific meanings.

Where is Llanddwyn Island?

Llanddwyn Island is located off the southwestern coast of Anglesey in north Wales. It is connected to the mainland by a sandy strip that floods only at the highest tides. The island contains the ruins of St Dwynwen’s church and is accessed via Newborough Forest.

Can you visit Llanddwyn Island?

Yes, Llanddwyn Island is accessible to visitors via Newborough Beach on Anglesey. The walk from the car park to the island is approximately one mile through forest and across the beach.

Is Santes Dwynwen Day a public holiday?

No, Santes Dwynwen Day is not a public holiday in Wales or anywhere else. It is a cultural celebration without official holiday status.

Do you have to speak Welsh to celebrate Santes Dwynwen Day?

No, you do not need to speak Welsh to celebrate Santes Dwynwen Day. While Welsh language is central to the celebration, non Welsh speakers can participate by exchanging cards and gifts, learning a few Welsh phrases, or simply marking the day as an occasion for expressing love.

What gifts are traditional for Santes Dwynwen Day?

Traditional gifts include Welsh lovespoons, cards featuring Welsh language greetings, Welsh food and drink, and other items with Welsh character. Flowers, jewellery, and other romantic gifts are also appropriate.

When did Santes Dwynwen Day become popular?

The modern revival of Santes Dwynwen Day began in the late twentieth century and gained significant momentum in the twenty first century. The celebration has grown substantially since the 1990s to become a recognised part of the Welsh cultural calendar.

What is the legend of Dwynwen and Maelon?

According to legend, Dwynwen fell in love with Maelon but could not marry him as her father had promised her to another. After divine intervention that included Maelon being turned to ice, Dwynwen was granted three wishes: that Maelon be restored, that she never marry, and that she become the patron saint of lovers.

What was Ffynnon Dwynwen?

Ffynnon Dwynwen was the sacred well on Llanddwyn Island associated with St Dwynwen. Medieval pilgrims visited the well seeking divination about their romantic futures, interpreting the movements of a sacred eel or fish as omens about their love lives.

Is Santes Dwynwen Day older than Valentine’s Day?

As a saint’s feast day, St Dwynwen’s Day dates from the fifth century when Dwynwen lived and died. The celebration of St Valentine dates from a similar early Christian period. The modern romantic celebration of Valentine’s Day developed primarily from the medieval period onwards, while the modern revival of Santes Dwynwen Day is largely a late twentieth and twenty first century phenomenon.

What does cariad mean?

Cariad is the Welsh word for love and is also used as a term of endearment meaning darling, sweetheart, or loved one. It is one of the most commonly used Welsh words in romantic contexts.

Wales Flag: Amazing Story Behind the Welsh Flag and Symbolic Strong Red Dragon

Welsh Words and Phrases That Make It the World’s Most Beautiful Language